Why is it that when a woman receives flowers – even daisies, roses or carnations – the first thing she does is “smell” them? Even if they don’t knowingly emit a fragrance?

Or how about when at a perfume counter where we’re presented with several new fragrances to test – we go to “smell” them? Why not just apply it first and then smell it?

Same goes for tasting foods – either we’re not going to taste something new at all or we are very stingy about the portion size; squint and cringe prior to the plunge.

Why such dramatic responses to something that would appear so slight?

After all; “that scent reminded me when I was sick” or “that smells like my grandmother – get that away from me!” or how about “that smell reminds me of the wonderful honeymoon we shared!”. Or “that tastes like my mother’s recipe and takes me back “. All tied up to the wonderment of life with positive or negative reactors.

Now a lot of people that I’ve spoken to – this doesn’t seem to affect them as much as it does me in the least. But then all of a sudden; those same people might react violently to a scent or a taste with a very powerful display of dissatisfaction. Why is that?

It is likely that much of our emotional response to smell is governed by association, something which is borne out by the fact that different people can have completely different perceptions of the same smell. Take perfume for example; one person may find a particular brand ‘powerful’, ‘aromatic’ and ‘heady’, with another describing it as ‘overpowering’, ‘sickly’ and ‘nauseating’. Despite this, however, there are certain smells that all humans find repugnant, largely because they warn us of danger; the smell of smoke, for example, or of rotten food.

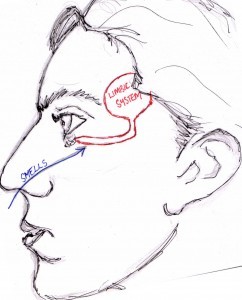

A smell can bring on a flood of memories, influence people’s moods and even affect their work performance. Because the olfactory bulb is part of the brain’s limbic system, an area so closely associated with memory and feeling it’s sometimes called the “emotional brain,” smell can call up memories and powerful responses almost instantaneously.

Here’s the reason why this happens:

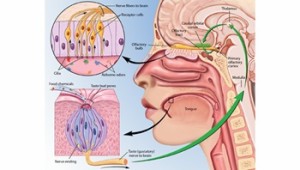

Upon detecting a smell the olfactory neurones in the upper part of the nose generate an impulse which is passed to the brain along the olfactory nerve. The part of the brain this arrives at first is called the olfactory bulb, which processes the signal and then passes information about the smell to other areas closely connected to it, collectively known as the limbic system.

The olfactory bulb has intimate access to the amygdala, which processes emotion, and the hippocampus, which is responsible for associative learning.

Despite the tight wiring, however, smells would not trigger memories if it weren’t for conditioned responses. When you first smell a new scent, you link it to an event, a person, a thing or even a moment. Your brain forges a link between the smell and a memory — associating the smell of chlorine with summers at the pool or lilies with a funeral. When you encounter the smell again, the link is already there, ready to elicit a memory or a mood. Chlorine might call up a specific pool-related memory or simply make you feel content. Lilies might agitate you without your knowing why. This is part of the reason why not everyone likes the same smells.

Now, take my father for a prime example. An authentic Italian thru and thru – just couldn’t stomach garlic! Really? An Italian that doesn’t like garlic? At one point in his life he had gotten sick from so much garlic and every time he tasted it – it reminded him of that incident. And he also couldn’t stand cloves and their taste. When he was a child and had teeth extracted or any dental work done (that happened to be very painful); a clove fragrant/tasting deadening agent was always used to numb his gums – so no cloves for him!

Smell is very highly emotive. The perfume industry is built around this connection, with perfumers developing fragrances that seek to convey a vast array of emotions and feelings; from desire to power, vitality to relaxation.

On a more personal level, smell is extremely important when it comes to attraction between two people. Research has shown that our body odor, produced by the genes which make up our immune system, can help us subconsciously choose our partners. Kissing is thought by some scientists to have developed from sniffing; that first kiss being essentially a primal behavior during which we smell and taste our partner to decide if they are a match.

With the knowledge that I’ve shared in this post….I will leave you with a couple of very profound writer’s rendition of how smells and tastes can define you….

From a writer’s point of view:

In Marcel Proust’s novel Swann’s Way, the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past, the narrator describes a day when he broke from his afternoon habit to have a cake called a petite madeleine dissolved in tea. “I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake,” he writes. “A shudder ran through my whole body, and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary changes that were taking place.” A feeling of “all-powerful joy” filled him; he knew it was connected to the tea and cake, but not how. He dug through his mind. Eventually, a memory emerged from the distant past. “The taste was that of the little crumb of madeleine which on Sunday morning at Combray … my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of real or of lime-flower tea.” Once he recognized the flavor, it all came back: “the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and its surroundings, taking their proper shapes and growing solid, sprang into being, town and gardens alike, from my cup of tea.”

Proust was fascinated with time and memory. In this famous passage, he describes how a flavor drags his character back to the past. Recent research has found the science to support Proust’s observations. The memories associated with smell — and the flavor of a food comes mostly from its smell — are more emotional and more likely to come from early life than memories evoked by other senses.

In many ways, a great dish is like a great memoir: in both, the salty, the bitter, the sweet and the tart must be in perfect balance to succeed. The memoir writer relies on nostalgia and sentimentality, but without horror and tragedy to leaven the sweetness, well, it wouldn’t be life, would it?

To some degree another famed author; Alfred Kazin depends on the reader’s memory of raw radishes and the hot heaviness of summer to evoke the sweet deliverance of his family’s well-chilled meal.

“In the sink,” he writes in “A Walker in the City,” “a great sandy pile of radishes, lettuces, tomatoes, cucumbers, and scallions broke up on their stark greens and reds the harshness of the world’s daily monotony. The window shade by the sewing machine was drawn, its tab baking in the sun. Through the screen came the chant of the score being called up from the last handball game below. Our front door was open, to let in air; you could hear the boys on the roof scuffing their shoes against the gravel. Then, my father home to the smell of paint in the hall, we sat down to chopped cucumbers floating in the ice-cold borscht, radishes and tomatoes and lettuce in sour cream, a mound of corn just out of the pot steaming on the table, the butter slowly melting in a cracked blue soup plate — breathing hard against the heat, we sat down together at last.”

Oh….the sweet memories — makes me want to write!!

Valerie